The Preacher, the Pilgrim & the President

The True History of Thanksgiving

“Give thanks unto the LORD, call upon his name, make known his deeds among the people.” – 1 Chronicles 16:8

An honest look at the history of how Europeans came to dominate the American continents reveals a series of stories that are mixed in their messages to our time. As 21st Century Americans we would do well to acknowledge the many credible accounts that demonstrate a mentality of conquest from Spanish, English and French settlers, and later from officials of national and state governments that did much damage to the native population of the “New World”. On the other hand, history is done a similar disservice by the ignorance and political reinventing of American history in efforts to further vilify the “white man” or promote some other agenda at the expense of an understanding that could help us as a people to internalize the lessons that can and should be learned from a genuine exploration of the difficult truths of those times, as well as those that can serve to inspire us today.

One of those stories that should serve to inspire, deserves a renewed focus, lest it fall to the unscrupulous push to rewrite it as another depressingly twisted and deliberately false account of tyranny. The true history of the Thanksgiving holiday is one that brings balance to the story of America, as it brings to light the miraculous role the hand of God played in establishing and sustaining the American principles that made it possible for us to be able to worship as we do, with little resistance from our government or our society. In turn, it can help us to be more grateful for God’s presence and miracles in our own lives.

We can see the story of Thanksgiving clearly through an exploration of the words and actions of three key players; a Preacher, a Pilgrim and a President.

The Preacher

The preacher’s name was John Robinson, the pastor from Holland who led a worship service for the separatist passengers of the Mayflower before their departure in 1620. The text of his message was Hebrews 11:13-16. Verse 13 concludes a 12-verse tour through the history of faith that brought the Jews to the promised land. From Abel to Enoch to Noah, to Abraham, then Isaac and Jacob, “These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth”.

Robinson was speaking to a people who had declared “plainly that they seek a country” (verse 14). The preacher wasn’t to accompany the Pilgrims on their journey to their “promised land,” but he had faith that God would bless their efforts. Perhaps in some small way, Robinson knew something miraculous would come of it. Despite the opposition they battled in Europe, the Pilgrims departed. The voyage itself across the Atlantic was a dangerous one. They were headed for Virginia, but ended up in Massachusetts.

The land and the natives in North America were not exactly friendly to Europeans at this time. A decade before the Pilgrims arrived, the colony at Jamestown failed. The first attempt at Jamestown was one of those dark times in which people died. They came from Europe grossly underprepared for what awaited them. Winter was harsh and disease became a deadly foe. Those were the months that are remembered as the “Starving Time.” They burned a bridge by failing to realize the value of a good relationship with the natives, who knew how to survive in those conditions. Those who were not taken by disease or hostilities with the Indians, survived by eating shoe leather or died trying.

Ten years later, when the Mayflower landed, it was already November. At first, things looked as bleak for the Pilgrims as they had for Jamestown. Before that winter was over, half of those living in the Plymouth colony would die, but God wasn’t done with them yet.

The Pilgrim

If not for the Pilgrim, William Bradford, we would know little to nothing about John Robinson, the beginning of the story in London and Holland, or the voyage across the ocean. Bradford’s writings are our main source for an understanding of how God saw the Pilgrims through that first chapter in their story, as well as that of how the Plymouth Colony survived through a series of miracles.

It was a cold November in 1620, but somehow when the Mayflower arrived, the Plymouth area was already cleared and ready to settle. Four years earlier a Pawtuxet tribe was wiped out by a mysterious plague. The neighboring tribes didn’t bother the Plymouth Colony because they believed the area to be cursed by some supernatural spirit. Bradford found out about this when an English-speaking Indian named Samoset arrived with the story. He welcomed the Pilgrims and introduced them to Squanto, a survivor of the Pawtuxet who also spoke English.

The event we look back to as the first Thanksgiving dinner in October 1621 was bountiful. Squanto had taught the Pilgrims how to raise corn, plant pumpkins, refine maple syrup, pick medicinal herbs, harvest beaver pelts and catch eels and fish. Unlike the disaster at Jamestown, Plymouth was a picture of cooperation. A meal of gratitude and friendship was shared between the devoted Christian Pilgrims and a pagan native tribe.

Just as John Robinson before him, William Bradford affirmed in his writings the Pilgrim belief that America was their “Promised Land”. This is clear from Bradford’s reference to Deuteronomy 34:1-4, wherein God showed Moses “all the land” that He would be giving to Israel as He had promised to Abraham. Contrary to 21st century wisdom, this vision in its purist form was not in conflict with any claims the natives had on the land. The natives did not have the same concepts of land ownership that the Europeans had. Peaceful, cooperative co-existence was a perfectly plausible plan that worked to the benefit of both the natives and the white man, until greed, corruption and violence interfered.

For a moment in time, some godly people understood this, but as time passed only a few held onto it. Even William Bradford lost sight of it. For centuries now, fewer and fewer have been able to see how God blessed America’s beginnings, and even fewer have understood how much more blessed America’s history could have been. Thankfully, among those few were at least a couple of Presidents.

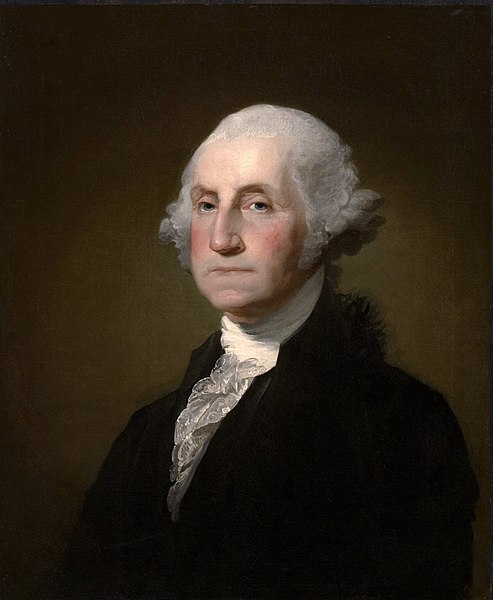

The President

From Colonial times to the Civil War, much can be said of the flaws and failures of American men, and even wickedness in high places among them. But through it all, we can still be thankful for God’s hand in sustaining a level of freedom that no other nation enjoyed.

On July 9, 1755, at the height of the French & Indian War, Colonel George Washington was among 86 officers in battle at Pittsburgh. During the battle, Washington carried orders on horseback among the officers. Of 86 officers, Washington was the only one who was not shot down off his horse, though several horses had been shot from under him. He later found four bullet holes in his coat, yet not a scratch on him. A later account from an Indian chief who was on the opposing side, says that the chief had ordered his braves to shoot down officers; that he personally had shot at Washington 17 different times without effect. The chief attributed this to what he viewed as a spirit that was watching over Washington.

The well-known events at Valley Forge during the Revolution give credence to this story, as Washington is known to have gone to God on his knees on behalf of his troops in the middle of the night. His men were tired, cold and hungry. Many were dying of disease. They were in dire need of provisions, food, boots and medicine, and Washington feared the infant nation was on the verge of losing its costly bid for independence.

George Washington saw God come through for America in such a miraculous way that he never forgot it. On October 3, 1789, President George Washington issued his Thanksgiving proclamation:

“Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor—and whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me ‘to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.’”

This marked the first national celebration of the holiday that has become commonplace in today’s households.

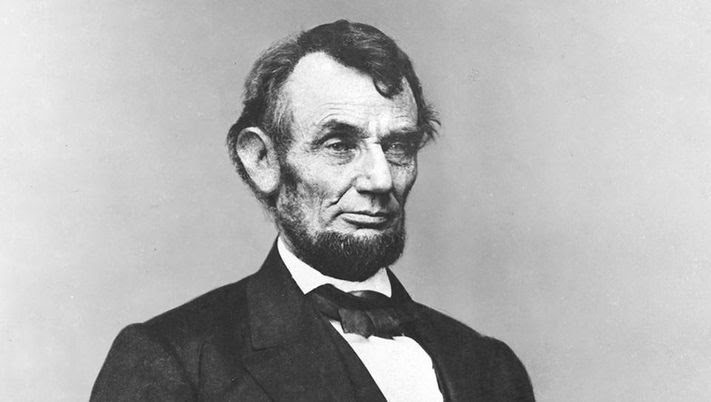

In the years that followed, the abomination of Slavery continued to be at odds with the constitution’s principle of states’ rights. This internal conflict came to a violent head when another man of God took our nation’s highest office. There can be little doubt that Lincoln believed the Bible. “In regard to this Great Book,” he once said, “I have but to say, it is the best gift God has given to man. All the good the Savior gave to the world was communicated through this book. But for it we could not know right from wrong. All things most desirable for man’s welfare, here and hereafter, are to be found portrayed in it.”

Furthermore, few have dared argue that Abraham Lincoln served the God of the Bible, and humbly sought God for wisdom. He said, “I have been driven many times upon my knees by the overwhelming conviction that I had no where else to go. My own wisdom and that of all about me seemed insufficient for that day.” Indeed, Lincoln truly desired to honor God with his leadership at a time when America’s survival as a nation was perhaps at its most fragile. He made this clear in a speech at Peoria, Illinois on October 16, 1854: “Near eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for SOME men to enslave OTHERS is a ‘sacred right of self-government.’ These principles can not stand together. They are as opposite as God and mammon; and whoever holds to the one, must despise the other.”

In the heat of the Civil war, the country still threatening to tear itself apart, the 74th anniversary of Washington’s original proclamation came around. The significance and meaning of which was not lost on Lincoln. On October 3, 1863, he made it permanent when he ordered that the last Thursday of November would be set aside as a day of Thanksgiving and praise.

And so it is that in our own history and heritage, God has planted reminders to be thankful for the great things He has done in our past, the miraculous things He is doing in our lives now, and the promise of glorious things for the future.